Solution to America’s Growing Energy Crisis?

By Ivan Penn and Malika Khurana Sept. 27, 2025

For years, Dan Harrison’s home in the western hills of Los Angeles would lose power when it was hot, when it rained or when it was very cold — sometimes the outages would stretch longer than 10 hours.

So, he took matters into his own hands.

Over the last six years, he has bought rooftop solar panels and batteries. Now, his house often helps keep the lights on across his neighborhood, near the University of California, Los Angeles.

U.S. electric grids are increasingly under strain and utility companies are spending tens of billions of dollars on upgrades — expenses that are driving up electric bills. At the same time, power-hungry data centers, electric vehicles and heat pumps are increasing demand for electricity.

But adding new sources of power isn’t easy. Turbines for natural gas plants are scarce. Large wind and solar projects and the transmission lines to connect them to cities are often stymied by local opposition. New nuclear reactors are years away.

One solution is to install more rooftop solar panels and batteries. Each such system is small, but collections of them can act like small power plants by supplying electricity to the grid when demand surges on, say, summer afternoons.

“This is a customer-led way to improve lives,” said Mary Powell, a former utility executive who is now the chief executive of Sunrun, the nation’s largest rooftop solar and home battery company.

But not everybody buys that idea. President Trump has criticized solar and wind energy as unreliable while championing fossil fuels. Congress is ending tax benefits for solar, and the administration is scrapping a $7 billion program that helped low-income families install rooftop panels.

It’s not just Republicans who have targeted such energy systems.

Even in California, regulators have limited rooftop solar’s growth in favor of large energy projects.

Consumers are now rushing to install systems before a federal tax credit goes away next year.

“This is a customer-led way to improve lives,” said Mary Powell, a former utility executive who is now the chief executive of Sunrun, the nation’s largest rooftop solar and home battery company.

But not everybody buys that idea. President Trump has criticized solar and wind energy as unreliable while championing fossil fuels. Congress is ending tax benefits for solar, and the administration is scrapping a $7 billion program that helped low-income families install rooftop panels.

It’s not just Republicans who have targeted such energy systems.

Even in California, regulators have limited rooftop solar’s growth in favor of large energy projects.

Consumers are now rushing to install systems before a federal tax credit goes away next year.

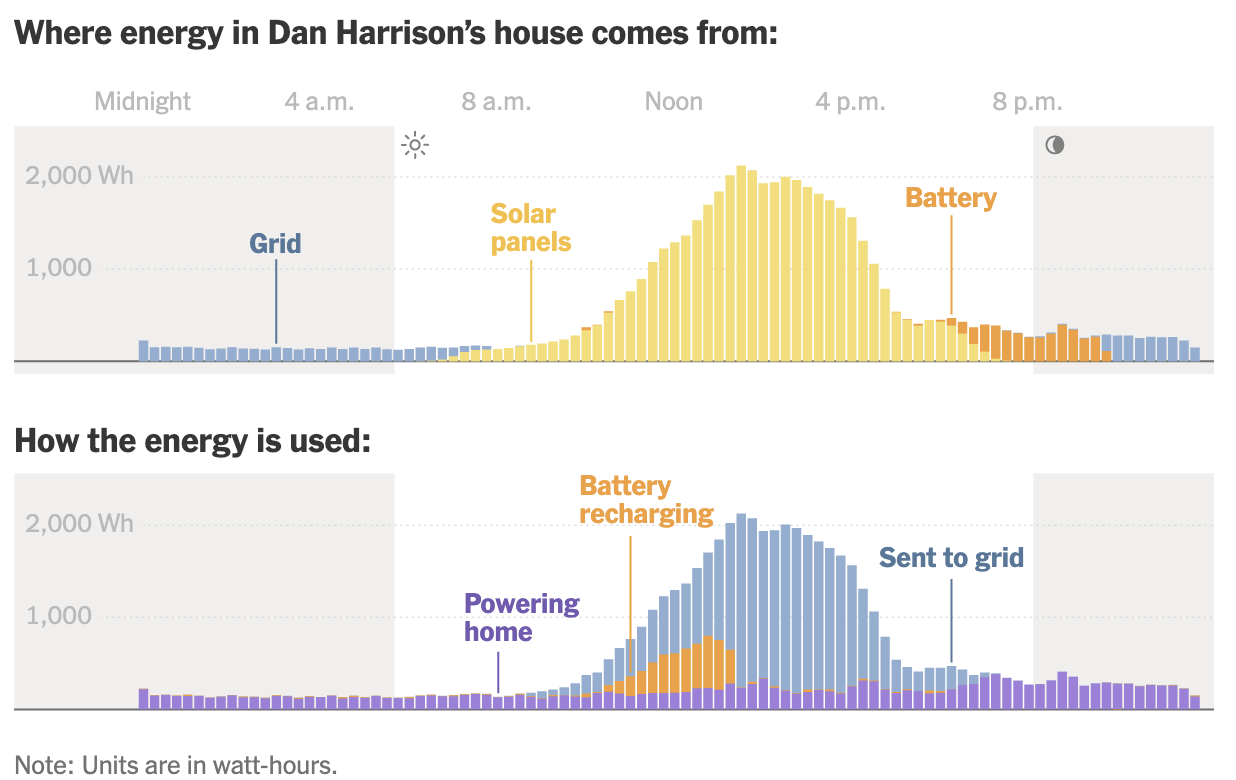

Almost three dozen panels blanket Mr. Harrison’s roof and begin producing electricity after dawn. In the early hours, all of that energy, plus some from the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, feed his appliances and lights.

As the sun gets brighter, the panels start generating more power than Mr. Harrison, 55, an entertainment television executive, and his wife and daughters can use. Some automatically goes into three batteries.

Electricity from his panels also flows onto the utility’s power lines.

Like water running down a hill, the energy moves along the path of least resistance, meaning it goes to his neighbors.

A few dozen panels on several roofs can provide a lot of power.

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory concluded in a 2016 report that rooftop systems could theoretically provide almost half of the electricity that residents in many states use over a year and as much as 74 percent in sunny California.

Rooftop systems can be installed relatively quickly, and they generate energy that doesn’t travel far.

The downside is that installing rooftop panels costs more per kilowatt of energy than putting panels in open land.

Whether rooftop solar is good for U.S. energy systems depends on how those trade-offs are analyzed, said Severin Borenstein, the faculty director at the Haas School of Business’s Energy Institute at the University of California, Berkeley.

“The question is how do we meet growing demand” for electricity, Mr. Borenstein said. “How much will demand grow and how much will it create a strain on the grid. How fast can you build out grid-scale solar, which is, and not open to debate, cheaper?”

Ms. Powell noted that the more than 130,000 systems enrolled in Sunrun’s distributed power plant program have enough capacity to keep the electricity flowing to 480,000 homes. On June 24, when electricity demand was high, the company deployed about half of that capacity to help grids in California, New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Puerto Rico.

Calvin Butler, the chief executive of the utility company Exelon, who is also the chairman of Edison Electric Institute, an industry association, agreed that rooftop solar can help grids. But he said the industry needed to figure out how to roll out such systems efficiently.

“I’ve never met an idea that I didn’t want to dive into and to put in place, if it was going to get our customers up sooner rather than later and the security and the resiliency of the grid wasn’t going to be jeopardized,” Mr. Butler said. “Part of that becomes the distributed power plant or virtual power plant, just scaling that up.”

In the afternoon, Mr. Harrison’s panels are very productive. But the house is mostly empty and does not use much power.

As a result, most of that electricity is going into the batteries or to neighbors.

Many experts consider this surplus a problem. When too many rooftop solar systems are producing lots of electricity, some utilities have to order large solar farms and natural gas plants to scale back to reduce the risk of overloading the grid.

“Putting on solar without a battery, does almost nothing to help” the energy system, Mr. Borenstein, the Berkeley professor, said.

About three years ago, California significantly reduced subsidies for rooftop solar panels while offering more incentives for batteries.

But batteries are rarely sufficient enough to fully meet a typical family’s needs because most can supply just four hours of a home’s electricity use.

When its very hot or very cold, residential energy systems usually don’t cover an entire 24-hour period. In California some properties can operate off the grid, but they require large, expensive systems.

Solar energy is expected to supply about 7 percent of U.S. electricity this year and 8 percent next year, up from less than 1 percent 10 years ago. Rooftop systems produced a fraction of that, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. In California, utility-scale solar delivers about a fifth of the state’s electricity, and rooftop systems add another 10 percent, according to the California Solar & Storage Association.

State regulators and utilities contend that without safeguards, rooftop installations can increase energy costs. They say that if too many people join Mr. Harrison in zeroing out their utility bill, much of the cost of maintaining the grid will fall on renters and others who cannot afford solar panels.

In 2023, California’s Public Utilities Commission sharply reduced the value of the credits for new solar systems.

“Solar energy systems are installed on more than 1.8 million California homes and businesses, exceeding the state’s goal to install one million solar roofs,” the commission said in a statement. “But this support has come at a cost to California ratepayers.”.

As the evening begins, Mr. Harrison’s home is drawing energy from his batteries and the grid. This can bring its own challenges.

Big banks of batteries and natural gas power plants have to crank up in the late afternoon as people start using appliances, lights and other devices.

In Mr. Harrison’s case, the grid has not always been reliable.

For years, the power lines, poles and transformers on the aging circuit, known by the number 135-22, that serves his neighborhood, increasingly became overloaded.

Energy experts say similar problems exist around the country because utilities spent too little on maintenance over decades.

The city’s Department of Water and Power acknowledged that its system, including circuit 135-22, needed upgrades. In 2023 and 2024, the agency spent $1.4 billion improving poles, wires and transformers. Each circuit typically supplies power to about a thousand residences. The utility has 1.6 million customers in total.

“Over the past five years, LADWP has undertaken significant upgrades to reduce outages and prepare its grid for the growing adoption of solar, battery storage and electric vehicles,” Mia Rose Wong, a utility spokeswoman, said. “Mr. Harrison’s experience, though unfortunate, highlights the benefits of LADWP’s infrastructure investments.”

But in early 2020, before his circuit was upgraded, Mr. Harrison installed solar panels, joining many others; about 85,000 Los Angeles homes have rooftop solar, according to the utility. Mr. Harrison spent about $26,000 on his panels before taking into account federal tax credits.

But he still lost power, because almost all solar systems are designed to stop operating when the electric grid goes down unless they are tied to a battery.

In 2020, over Labor Day weekend, the Harrisons had no electricity for 26 hours. A week later, he had one battery installed and then two more. The batteries cost around $14,000 before tax credits.

In addition to using the batteries for backup power, Mr. Harrison often makes up to 50 percent of his household’s capacity available to the grid.

Even in the evening, as solar energy wanes, Mr. Harrison’s system keeps chugging along. On a recent day in June, it sent energy to the grid until after 7 p.m., and the house was powered almost entirely by battery until nearly 10 p.m.

“It’s the one-two punch you need to solve the climate crisis,” said Omar Nasser, the founder of Treepublic Solar, the firm that installed Mr. Harrison’s system with equipment from Enphase.

For Mr. Harrison, the environmental benefits are an added benefit to having peace of mind. “Now,” he says, “I don’t even notice if the power goes out in the neighborhood.”

Sources

Home energy data was recorded every 15 minutes on June 12, 2025, in Los Angeles and provided by Enphase.

Solar panel adoption data counts each single-family home with rooftop solar panels and covers 70 percent of the U.S. population. Data provided by CAPE Analytics, a Moody’s company, and produced from imagery captured by Vexcel Imaging, EagleView and other providers. Population data from U.S. Census Bureau, 2019-2023 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates.